The illegal trade in elephant tusks is well reported, but there’s a type of “ivory” that’s even more valuable. It comes from the helmeted hornbill – a bird that lives in the rainforests of East Asia and is now under threat, writes Mary Colwell.

It wouldn’t be wise to go head to head with a helmeted hornbill. The helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) is a very large bird in the hornbill family. They weight 3kg and have their own built-in battering ram – a solid lump of keratin (a fibrous protein) extends along the top of the bill and on to the skull. This “casque” can account for as much as 11% of a bird’s weight.

In all other species of hornbill – there are more than 60 in Africa and Asia – the casque is hollow, but the helmeted hornbill‘s is solid. The males use it in head-to-head combat and both sexes use it as a weighted tool to dig out insects from rotting trees.

Helmeted hornbills live in Malaysia and Indonesia. On the islands of Sumatra and Borneo their maniacal calls and hoots resonate through the rainforest. They tend to eat fruit and nuts and are often referred to as the “farmers of the forest” as they spread seeds widely in their droppings.

They have a wingspan of up to 2m (6ft 6in), striking white and black feathers and a large patch of bare skin around the throat. They have a reputation for being secretive and wary, though, and you’re more likely to hear them than see them.

They have good reason to be shy – thousands are killed each year for their casques, shot by hunters who sell the heads to China.

Between 2012 and 2014, 1,111 were confiscated from smugglers in Indonesia’s West Kalimantan province alone. Hornbill researcher, Yokyok Hadiprakarsa, estimates that about 6,000 of the birds are killed each year in East Asia.

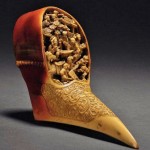

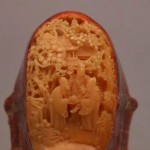

The casque, for which hunters are willing to risk arrest and imprisonment, is sometimes referred to as “ivory”. It’s a beautiful material to carve, smooth and silky to the touch, with a golden-yellow hue, coloured by secretions from the preen gland – most birds use their heads to rub protective oils from this gland over their feathers, legs and feet.

For hundreds of years it was highly desired by Chinese craftsmen who made artefacts for the rich and powerful, and by Japanese netsuke carvers who made intricate figures for the cords on men’s kimonos. Many of these objects made their way to Victorian cabinets in the UK when netsuke collecting became fashionable in the 19th Century.

“There are some records that showed the hornbill ivory was presented to the shogun,” says Noriku Tsuchiya, curator of the Japanese section at the British Museum. “Unfortunately by the early 20th Century the hornbill became very rare because of hunting and now legal trade is limited to certified antiques.”

Illegal it may be, but trade continues undercover, and hornbill ivory is worth about £4,000 ($6,150) per kilogram – three times more than elephant ivory. The killing of Africa’s elephants and rhinos for their tusks and horns is well reported, but the helmeted hornbill’s plight often slips under the radar. “If no-one pays attention, this bird is going to become extinct,” warns Hadiprakarsa.

The helmeted hornbill has been culturally significant for thousands of years – it serves as the coat of arms of the Malaysian State of Sarawak and is the mascot of West Kalimantan. The Dayak people of Borneo believe the bird ferries dead souls to the afterlife, acts as a sacred messengers of the gods and consider it a teacher of fidelity and constancy in marriage. Killing it is taboo.

But it’s not just hunting that threatens this slow breeding creature – its habitat is also under pressure. As the appetite for palm oil grows in the West, developers are encroaching on Asia’s rainforests. Researchers at the National University of Singapore estimate that Borneo and Sumatra are losing nearly 3% of their lowland rainforest every year.

As a result, the helmeted hornbill “is considered Near Threatened, and should be carefully monitored in case of future increases in the rate of decline,” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

So the bird faces a double whammy – losing its head to ivory carvers and its home to supermarket products. I’m not sure I fancy its chances.

Source : BBC news

Photos credit : Doug Janson & various online sources